Feat of the Week: Dazzle Camo

The Gunsmithing Story

This week’s feat is a fully customized Sig P320 X Five Legion with an Icarus Precision Ace Frame, custom slide machining, and custom Dazzle Camo Cerakote. The customer requested something over-the-top for his gun—both slide milling and Cerakote. And we gave him just that. We can’t wait to tell you more about it. So let’s get started!

To meet the customer’s request, we decided to give his slide two different cuts. First, to create some dimension at the barrel, we designed and milled a “Nose Cut.” We also wanted to create something new for him. So, we decided to CAD a flashy type of window cut for the side of his slide. We designed three three-sided windows increasing in length but decreasing in angle—we call these “Crescendo Cuts.” We made sure the angles matched the Nose Cut and the lengths matched the top window cuts. These details bring the entire slide together and make it look like one cohesive design.

Next, we took on the task of painting an insane Cerakote pattern.

The Cerakote Story

We wanted to give this gun a little Razzle Dazzle—a ridiculous pattern of chaotic, intercepting lines complemented by green accents to make it pop. And we couldn’t be happier with the result. This thing looks amazing.

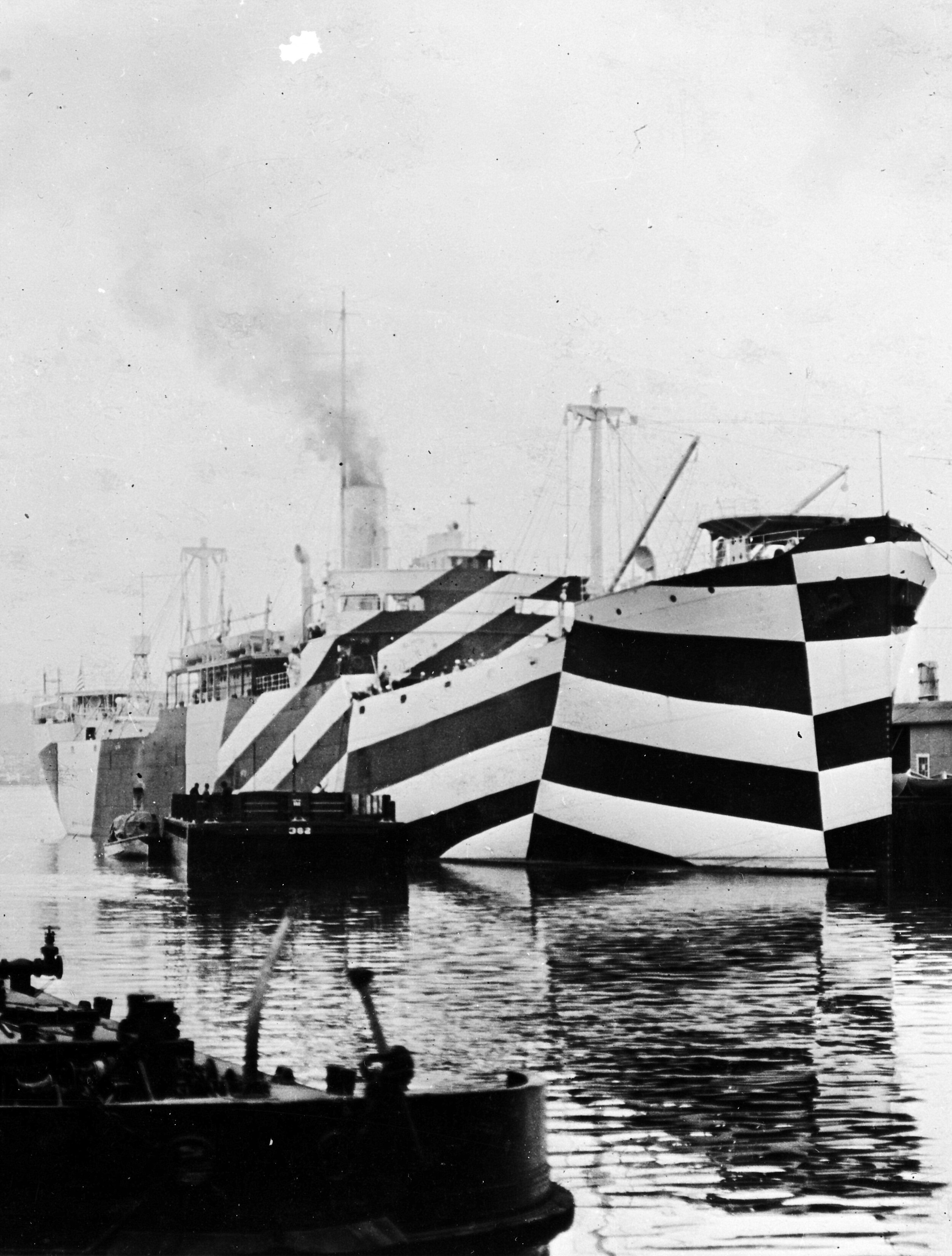

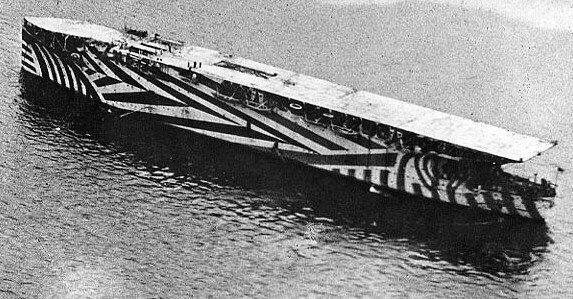

It’s reminiscent of something out of Alice in Wonderland or even A Clockwork Orange. But this pattern, known as Dazzle Camouflage, was actually a maritime paint design used on U.S. and British naval ships during World War I and World War II.

Dazzle Camouflage came from a desperate need to conceal or obscure British merchant ships and Navy vessels during World War I. When the British lost several merchant ships at the hands of German submarines, Dazzle Camo was put into action to better protect ships from attack.

In 1914, a British zoologist John Kerr had proposed a parti-coloring, disruptive camouflage for British ships. Citing years of research on animal patterns and shading, such as those on giraffes and zebras, Kerr wrote to Churchill describing the pattern. He intended to use a similar pattern to confuse the enemy by disrupting the ship’s appearance and outline. Just a year later, Abbott Thayer, an American artist, also wrote to Churchill suggesting a similar proposal and a theory about disruptive colors and countershading seen in the animal kingdom.

But Churchill ignored both propositions. In 1917, he chose Dazzle Camouflage instead—a non-scientific and less advanced pattern invented by British artist Norman Wilkinson.

With a Cubist aesthetic, this wartime camouflage drew the attention of Picasso. Cubists, Picasso claimed, invented Dazzle Camouflage. He didn’t mean this literally, but rather that Dazzle is characteristically Cubist.

It was around this same time that Cubism and Picasso were taking off in Europe. The first popular exhibition and curated show was 1912. And by World War I, Cubism had become a known artistic style and movement characterized by flat, overlapping geometric lines. It is interesting then, to learn that all of the British Dazzle designs were first tested on small models painted at the Royal Academy of Arts and that many of the patterns were created by artists.

Obviously, this camo doesn’t conceal much. In fact, it makes it stand out more. The complex and interrupting geometric pattern was intended to create confusion about the ships’ size, speed, and direction. For example, the patterns would create confusion between the bow and stern. One German U-boat Captain said, “The dark painted stripes on her after part made her stern appear her bow…The weather was bright and visibility good; this was the best camouflage I have ever seen.”

Every ship had its own dazzle camouflage pattern. This prevented their enemies from identifying a certain ship class based on its pattern.

And yet concrete evidence to suggest that Dazzle Cam was successful in achieving its goal was minimal. Studies conducted during and after the World Wars to determine the efficacy of the Dazzle demonstrated that it was no more useful than single color paint.

Nevertheless, over 4,000 British merchant ships, 400 British naval ships, and 1,200 U.S. warships were painted with Dazzle Camo during World War I. Even into World War II, it saw continued use but was later abandoned in the Pacific Theater to prevent Kamikaze attacks.

Though the efficacy of Dazzle Camo remains disputed—or unknown at best—this is one of our favorite Cerakote jobs to date. We hope you like it too.

Next Up

We hope you enjoyed this week’s gunsmithing feat. Thank you for following along! We post new blogs every Tuesday at 10am PST. Please comment for any content you want to see.

If you loved the services you saw today, check out our online store! You can start shopping by clicking here. Or drop us a message here. We look forward to meeting you and gunsmithing for you

Please subscribe to our blog below and don’t forget to follow us on social media!